This article is part of a five-part series on scoring insights that examines the role of GRESB Scores.

In this final installment of the insights series on GRESB Scores, we explore why these scores can be challenging to predict.

The GRESB Standards are used to evaluate the sustainability of real asset investments. While the GRESB Assessments have a lot in common with many other sustainability assessments, they also have some important differences. Notably, assessment outcomes can vary year over year, even when a given entity’s responses remain the same. These variations are not entirely predictable based on information available to an individual participant. This is a feature of the GRESB Assessments, not a bug. Really. Let me explain why.

Many sustainability assessments are static “scorecards.” Questions on these scorecards are independent from each other, and the award of points is independent from every other entity taking the assessment. The Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) green building rating system is a good example. LEED rating systems are composed of minimum requirements, prerequisites, and credits. In theory, each credit—the fundamental unit of assessment—represents a single aspect of practice or performance. The credit establishes a baseline expectation and then a level of practice or performance sufficient to warrant recognition as leadership. The credits are almost always evaluated independently, i.e., Energy & Atmosphere Credit 1 has no bearing on Water Efficiency Credit 1. And, the evaluation of a single credit is usually based on static criteria, such that the outcome of the evaluation is independent from every other project.

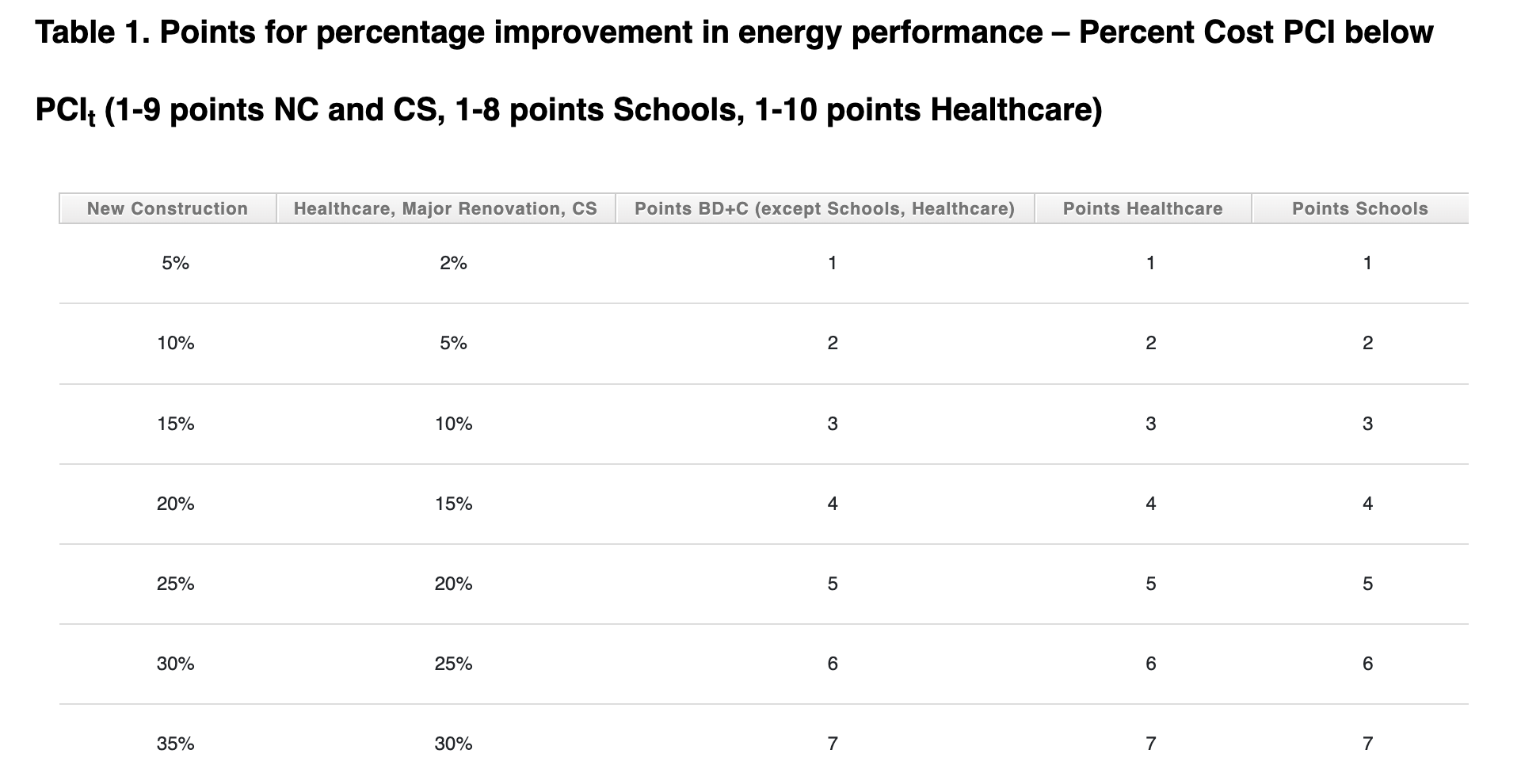

For example, a project pursuing LEED certification may be designed to exceed a baseline requirement by, say, 25%. This 25% target is compared to a static table of values. In other words, LEED version 4.1 references a specific energy code (e.g., ASHRAE 90.1-2016) and provides a set reward for a given level of outperformance. This condition can be evaluated independently regardless of the performance of any other building in the world.

This structure creates a stable, predictable rating system. It is possible, because the U.S. Green Building Council—the rating system’s governing body—operates a development process that explicitly establishes the baseline, along with “good, better, and best” levels of performance for every practice and performance metric in every rating system.

Figure 1. An illustration for the static relationship between energy efficiency design goals and LEED points (LEED Credit Library).

GRESB is a bit different. Established to assess the sustainability of real asset companies and funds, GRESB evaluates entities that are the aggregation of multiple parts, including management and a collection of discrete assets. These aggregations—companies and funds—do not typically have well-defined, generally accepted definitions for baseline and “good, better, and best” management or performance. There is no prescriptive standard for “good management” or widely accepted energy codes for portfolio energy efficiency. Consequently, GRESB uses benchmarking as a scoring rubric. “Good, better, and best” are defined in relative terms based on comparison to peer and benchmark groups. Benchmark-based scoring allows GRESB to interpret the performance of entities in the absence of the absolute standards used in green building rating systems.

The cost of the benchmarking approach is a lack of predictability. GRESB real estate uses benchmarking across multiple levels, first to score individual metrics (e.g., scores for data coverage) and then to rate whole entities (i.e., Stars). In practice, this means that the score for an individual metric or the rating for a whole entity depends on:

- The annual version of the GRESB Standard, which usually evolves incrementally from the previous year

- The population of entities participating in the assessment, which usually changes from the previous year

- The characteristics of an individual entity, which are usually subject to incremental change as well

Unfortunately, all three of these elements tend to change each year. The combination of these three moving parts means that it is not possible to assign a score to an indicator or a rating to an entity until all entities have submitted all information for a given year. In essence, everything is interconnected. It’s important to recognize that this is a smart solution to a tough problem, specifically the lack of relevant, accepted definitions for good, better, and best practice and performance. It’s equally important to remember that this creates fundamental limits to predictability.

Let’s compare these two approaches with an analogy: a running race. In the first race, the green building rating system race, the competitors line up for the hundred-meter dash. The course is accurately measured, laser-leveled, and fitted with precision timing equipment. In this scenario, a single runner starts and sprints down the track. The runner’s time is compared to absolute standards, >15 is poor, <12 seconds is good, and <10 seconds is great. This assessment can be made with only one runner present, and it is not contingent on anyone else’s performance. This is more-or-less the idea with try-outs for American football. Prospects run the 40-yard dash, and all the relevant people knows what the numbers mean.

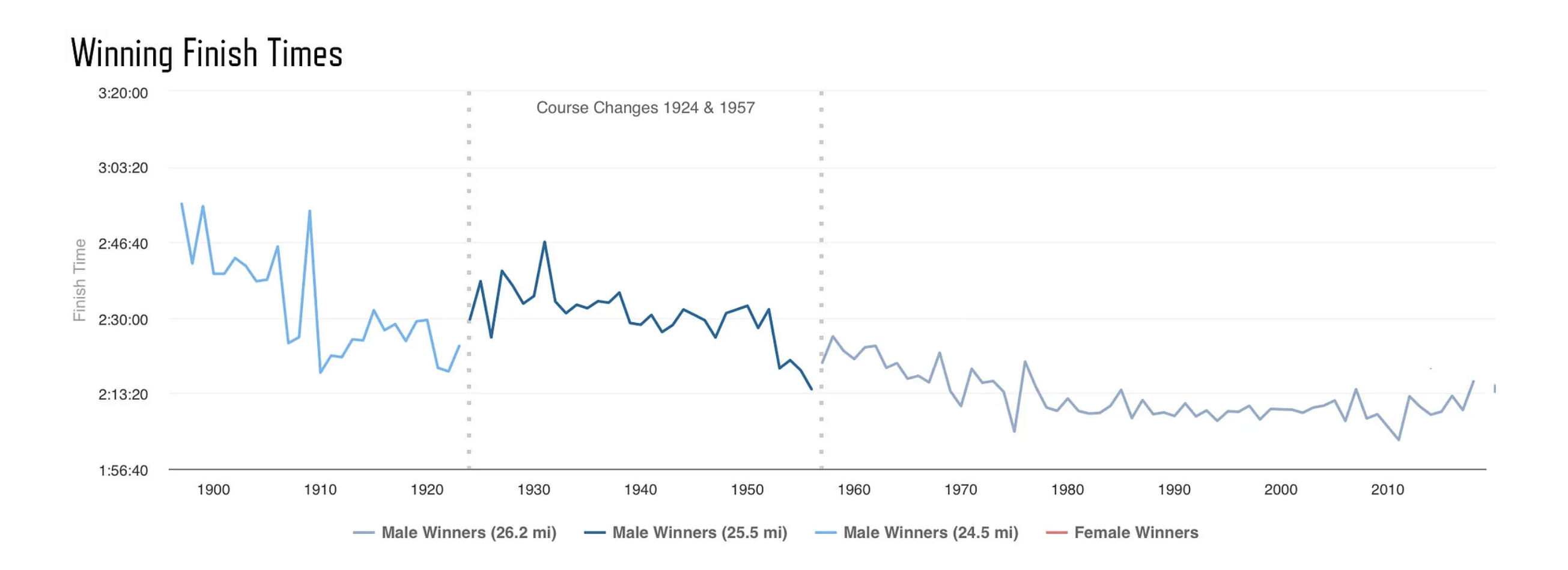

On the other hand, let’s consider the GRESB “race,” something closer to a marathon. In this case, the absolute time is usually less of an issue. Each marathon course varies with unique combinations of terrain and weather. It is hard to say if a time of 2:05, 2:10, or even 2:20 may win the day. Figure 2 illustrates the wide range of winning times in the Boston Marathon men’s open division since 1897. In this case, the relevant assessment is a benchmark—the position of the finishers against each other under the same conditions at that specific moment in time. Consequently, we celebrate first, second, and third place, not specific times.

Figure 2. Trends in Boston Marathon winning times between 1897-2018 (Source: Adrian Hanft, Boston’s Evolution: 1897–2018).

The bottom line for GRESB stakeholders is that GRESB’s lack of predictability is a feature, not a bug. It is a tool to compare practices and performance in situations where absolute standards are not available. It is also something that evolves over time. GRESB is looking for opportunities to replace benchmarks with absolute criteria. However, new and emerging issues constantly introduce new situations where benchmarking is a practical assessment strategy. The good news is that understanding the root causes of this unpredictability can help stakeholders better anticipate and adapt to changes. Additionally, GRESB is developing tools to hold parts of the benchmarking equation constant, enhancing both predictability and comparability.

At the end of the day, creating, operating, and interpreting a benchmark is a team sport. The GRESB team is here to help, and we hope this makes a dynamic process just a bit more predictable.