This article is part of a five-part series on scoring insights that examines the role of GRESB Scores.

This is the fourth article in a series of insights. We started with, “Why GRESB Scores?,” “Value beyond GRESB Scores,” and “What does a GRESB Score mean?”. The next question to explore is, “What does ‘comparable’ mean?”.

In this article, I want to answer this question in three ways: First, let’s consider the evolution of GRESB from assessment to standard. Next, we will consider comparability over time. Third, I will conclude by considering what comparability means for the real estate participants in 2024 and going forward.

From assessment to standard

GRESB is a different kind of “standard.” GRESB started—and, in many ways, still is—an assessment. It is a collection of indicators, metrics, and weights designed to collect, compare, and score disparate information about the management and performance of real estate companies and funds. This means it did not start out with the intention of being a traditional standard.

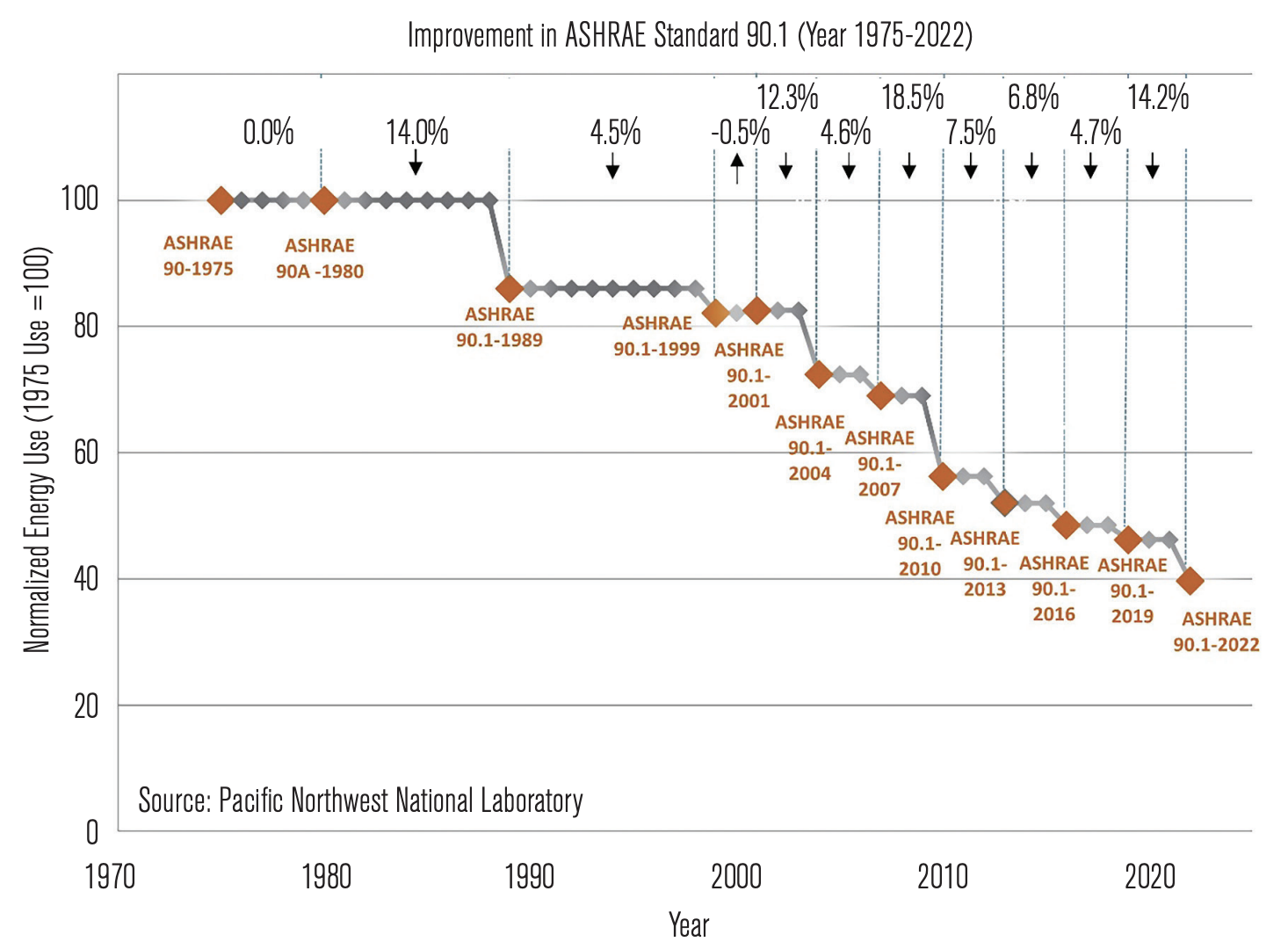

For example, the LEED green building rating system was created specifically to provide a consensus-based definition of the practices used to design and build a green building. LEED aligned with prevailing practice in the architecture, engineering, and construction industry with a conceptual goal of incremental changes in requirements every three to five years (e.g., the pace of change for something like ASHRAE 90.1). It also followed the paradigm by allowing projects to “lock in” a version of the standard when they “register” and use that standard for (effectively) however long the development process required. This created a situation where versions overlap in time. Stakeholders need to be familiar with changes between, say, v2.1, v2009, v4, and v4.1, in order to interpret requirements and compare stringency over time. This can be done, but it isn’t easy.

GRESB was inspired by various standards, including ISO 14001, the Global Reporting Initiative, CDP, and many others. However, it was envisioned as an annual assessment process, more like a recurring survey, than a fixed standard. This meant that incremental annual changes were routine from the beginning and a compelling feature relative to traditional standards.

GRESB would quickly learn from experience, shaping indicators, answer choices, metrics, and weights to provide the most material information for real estate investors and managers. This also created challenges. The window of time between the end of reporting, finalized results, and demand for next year’s reporting standard was very tight—typically between August and October (90 days). No other major standard tries to do this, likely for very good reasons. However, this didn’t seem like a problem since GRESB was an assessment, not a standard. Assessments evolve to meet user needs, informed by their experience and changing priorities.

Over time, expectations for GRESB changed. It became more than an annual assessment. Companies interpreted it as a standard. They looked at the indicators and metrics as a collection of best practices and performance goals. This is understandable. They look like that, and they make sense—particularly in the absence of any other credible, globally applicable sector-specific standard. The hitch is that this shift from an annually improving assessment to standard comes with different expectations.

GRESB recognized these changing expectations. It created the GRESB Foundation to manage a standard, not just an assessment. This required creating processes and practices needed to manage change over time, including reconciling divergent, sometimes conflicting opinions. These processes were established in 2020 and 2021, and they operate today.

Comparability over time

Managers expect more consistency and stability from a standard than they do from a pure assessment or survey.

As a rule, standards change slowly. Standards—particularly in the real estate space—adapt incrementally over time with long periods devoted to communications and consultation. Additionally, standards traditionally have distinct versioning, for example, distinguishing ASHRAE 90.1-1975, 90.1-2004, 90.1-2007, 90.1-2010, 90.1-2013, 90.1-2016, 90.1-2019… 90.1.2022 (ASHRAE 2023). These versions represent the ongoing evolution of a single standard. All of the versions are focused on building energy efficiency; however, they vary in their approach and stringency. ASHRAE created an index to illustrate “normalized” energy use intensity across the versions. This index reflects changes in performance for idealized building prototypes across versions. There isn’t a practical way to compare the implications of different code versions for any specific real-world building, particularly across longer periods of time (e.g., ASHRAE 90.1-2001 vs. ASHRAE 90.1-2022). There are too many changes in technology, baselines, and scope.

The evolution of GRESB followed a similar pattern, albeit with changes every year instead of three- or four-year intervals. Year-over-year changes in GRESB reflect user feedback, investor priorities, emerging issues, and a myriad of small changes intended to address specific issues (e.g., usability, unusual circumstances, etc.). Periodically, GRESB makes bigger changes. These reflect more substantial changes in methodology, such as in 2020 and 2024. Like ASHRAE 90.1, the mission of the GRESB Assessment remains the same through the changes—facilitating constructive engagement between investors and managers—but the details of the assessment evolve. Unlike ASHRAE 90.1, GRESB has not yet established a single-metric index for evaluating these changes. This reflects, in part, the difference between the evaluation of a single-purpose standard (e.g., ASHRAE 90.1) and a multi-criteria assessment (e.g., GRESB). Trends in a building energy code, hopefully, are reflected in declining energy use intensity over time. Trends in an entity-level assessment are spread across a broad set of management indicators and performance metrics.

Comparability in 2024

With this context, let’s turn to the specific case of the 2024 real estate results. I will describe two ways to understand year-over-year comparability.

The first scenario focuses on the big picture. From a high level, the final results for the 2024 GRESB Real Estate Assessment are very similar to 2023 and in line with earlier year-over-year changes. Statistically, the overall results have the same median score (78 points) and very similar variance (approximately 15 points between the top and bottom quartiles). Moreover, more than 90% of the points available in the system have the same basis for scoring and data collection. This includes the stable core of management indicators which are achieved at a high rate and constitute 30% of the total top-line score. At a more granular level, year-over-year improvement trends for the whole set of participants follow historic patterns. By these measures, trends in the GRESB universe as a whole are comparable year over year.

The second scenario focuses on circumstances for any individual participant. The changes in the 2024 Real Estate Standard had important impacts on scoring individual companies and funds. Let’s focus on three specific changes:

- New methods to collect and interpret asset performance changes

- A shift in benchmarking strategy from regions to countries

- New methods to collect and interpret building certifications

First, members of the GRESB Foundation have prioritized asset-level performance. They want to know that the aspirations of entity management are realized on–the ground. GRESB reflected this priority in new assessment methods, collecting and scoring performance at the asset level. In theory, this should not have been a big change, but, in practice, the difference between aggregating and then scoring or scoring and then aggregating is quite significant. This change has modest impacts overall, but significant impacts on large, diverse portfolios (i.e., those where performance among assets varies substantially).

Second, the change to asset benchmarking was accompanied by a shift from regional to country benchmarking. In the early years, regional benchmarking helped GRESB create viable peer groups from a relatively small number of participants—aggregating companies across broader regions such as the Americas or EMEA. In 2024, thanks to the growth in participation allowed for the creation of peer groups within countries. On average, this change is neutral to the overall benchmark, with “winners” (entities in countries less competitive than regions) balancing “losers” (entities in countries more competitive than regions). However, outcomes for individual entities often do not reflect the average. Some entities are significantly impacted by this shift in benchmarking. For example, building certification levels in the UK are well above the regional average, meaning that benchmarking against UK peers sets a higher bar for scoring than a comparison to EMEA more broadly.

Finally, GRESB simultaneously introduced new methods to evaluate building certifications, with the primary impact in the final results stemming from the time discount or amortization schedule. This adjustment reduced the value of a certification over time. Again, on average, most certifications in the GRESB universe are relatively recent in relation to the new schedule, and recertification or operational certifications are common in some property types. However, in some segments, results vary significantly. The most divergent groups include those who (1) prioritize new construction (design) certifications and (2) do not historically pursue operational certifications. These conditions are common in build-to-suit arrangements or circumstances where asset managers cannot access tenant data, such as in many types of industrial or logistics property. Although these conditions apply to a small percentage of GRESB Participants, they represent an important fraction of investor-owned real estate.

These three factors combine to create a scenario where the GRESB Real Estate Benchmark as a whole is very similar year over year but outcomes for individual entities may vary significantly. The narrative above describes some of the most important factors in determining whether an individual entity will follow the average or see significant changes.

Bottom line

GRESB is in the business of driving and managing change. In 2024, the GRESB Real Estate Standard saw more change than in recent years. Entities experienced this change in different ways. Many entities saw year-over-year stability. A significant set of entities saw significant impacts.

This created a situation with both stability and variation. While these shifts may present challenges, they also signal the continued evolution of GRESB as a dynamic tool for fostering sustainability improvements in real estate.